The line between NFL draft hype and reality has grown irrevocably blurred, creating a funhouse mirror of speculation built atop speculation. The case of Shedeur Sanders became the most striking, most bizarre example over three excruciating days this weekend in which he morphed from expected first round pick to free-falling prospect to societal weather vane that had President Donald Trump weighing in.

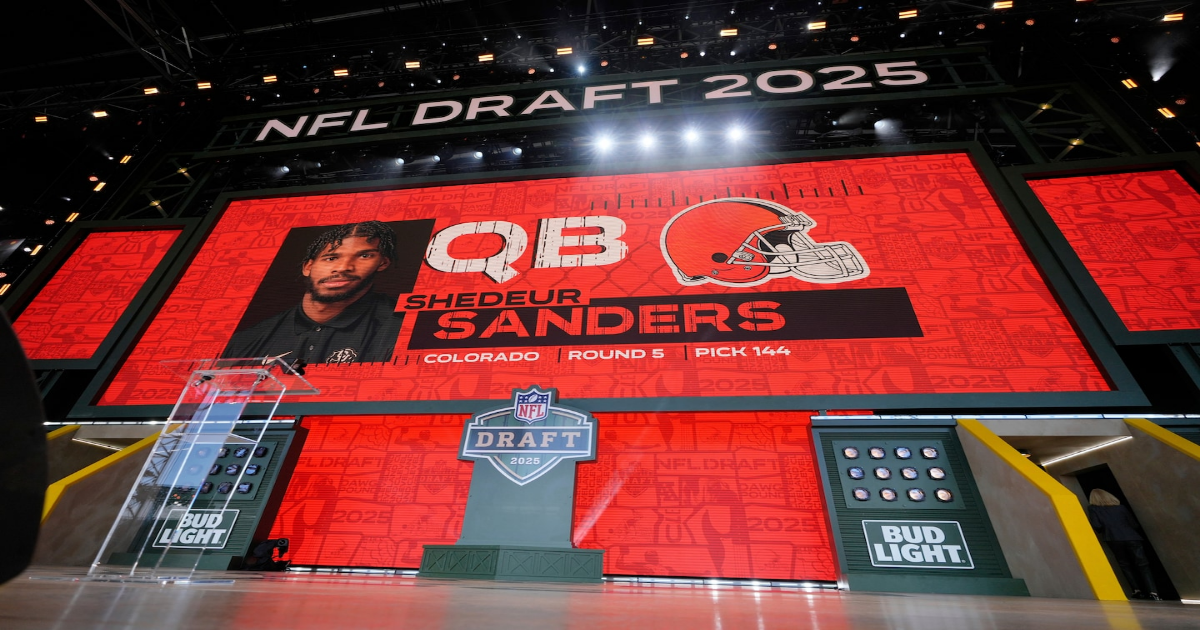

Sanders became the story of the 2025 draft for not being drafted. He waited until the Cleveland Browns — who had already taken a quarterback, the lightly regarded left-hander Dillon Gabriel, two rounds earlier — picked him in the fifth round with the 144th pick. His perceived slide prompted more questions than concrete answers.

Did Sanders fall? Or did the hype about his NFL prospects in the pervasive buildup to the draft always exceed the reality of how teams viewed him? Did the league rebuff Sanders because teams viewed him as an inadequate football player? Or were they wary of the potential disruption his last name could bring?

In public, Sanders was entrenched at the top of mock drafts for months, a facade that began to crack in recent weeks. Within NFL front offices, it’s now clear, he was viewed as a mid-round prospect who lacked elite athletic ability and arm strength. But nobody excepted him to fall into the middle of the third day of the draft. His fall turned from predictable to stunning to sad. There was no smoking gun explanation, just a stew of factors that melded into an all-time saga indicative of how the draft is covered and the uniqueness of Sanders as a prospect.

* Based on his college stats and production, Sanders might have looked like a first-round slam dunk. He won the Big 12 Offensive Player Player of the Year award, completed 71.4 percent of his passes over two seasons at Colorado, passed for 4,134 yards last year and finished eighth in Heisman Trophy voting. He was a major force in leading Colorado from the bottom of college football’s highest level to national relevance.

But NFL teams don’t draft based off stats and production. Syracuse’s Kyle McCord led the Football Bowl Subdivision with 4,779 passing yards and finished 10th in Heisman voting, and he lasted until the Philadelphia Eagles drafted him in the sixth round. Scouts and front offices look for traits and attributes that will translate to the NFL.

In Sanders’s case, his slow release led to him taking 42 sacks last year, the most in college football. Acknowledging Colorado’s lackluster offensive line, a high sack percentage has been a damning indicator for quarterback prospects. Sanders also lacks exceptional physical attributes. He’s relatively short at 6 feet 1. He ranked 14th in his quarterback class in NFL NextGen Stats’ athleticism score. His arm strength and speed are serviceable.

He has plenty of positive characteristics, especially his football intellect, passing accuracy and ability to feather throws between layers of defenders. But he doesn’t have the raw skill evaluators envision in a quarterback who can compete with Josh Allen and Patrick Mahomes.

* There are some within the league who believe Deion Sanders, who effectively acted as his son’s agent, mishandled and miscalculated the draft process. Rather than accepting how the NFL viewed Shedeur, some think he tried to manipulate and shape the evaluation. In a March 2024 appearance on a Barstool Sports podcast, Deion predicted either Shedeur or Colorado two-way star Travis Hunter would be picked first, and the other would be chosen fourth at the latest. He openly discussed refusing to sign with an undesirable franchise, a maneuver Eli Manning and his famous father, Archie, executed during the 2004 draft.

“There are certain cities where it ain’t gonna happen,” Sanders said. “It’s going to be an Eli.”

Deion continued to say he would not let his son play for certain franchises, including during media interviews during the week of the Super Bowl in February. His bluster — and perhaps high-placed media connections as a former television analyst — helped create the impression that Shedeur Sanders would be chosen at the top of the draft.

Meanwhile, even if NFL teams did not rate Shedeur Sanders as a first-round talent, his camp, led by his father, still clung to the idea he was. At some of his team meetings at the combine, according to multiple reports, the quarterback exhibited disinterest and a lack of professionalism.

* Beyond the draft process, Deion Sanders’s presence created questions. Shedeur Sanders has never played under a head coach other than his father. Deion Sanders’s decision to retire his son’s number at Colorado didn’t diminish the notion that Shedeur Sanders had a sense of entitlement. Even at Colorado, Deion Sanders is a constant and loud presence in the NFL’s media landscape. Shedeur Sanders himself has a podcast (title: “2Legendary”) and a camera crew following him around. Whether those concerns turn out to be legitimate or misplaced remain to be seen. But they were there, and they contributed to Shedeur Sanders’s fall.

* Once teams deemed Sanders unworthy of a first-round pick, a serious fall became far more possible. Coaches may have been willing to accept the trappings of Shedeur Sanders’s fame and his father’s spotlight for a franchise quarterback. For a player projected as a possible future starter or a backup, it was an unnecessary headache. It would be fair to wonder whether some decision-makers were also operating from a sense of fear that the presence of Shedeur Sanders — and the looming presence of his father — could threaten their job security.

* Quarterback is a unique position. Teams can stack linemen, pass rushers or wideouts in a way that’s not feasible with quarterbacks. Technically, teams passed on Sanders 143 times. Practically, how many opportunities did he have to be taken? The Bills, Patriots, Ravens, Bengals, Texans, Jaguars, Chiefs, Chargers, Broncos, Eagles, Commanders, Vikings, Packers, Bears, Buccaneers and Falcons — half the league — had no conceivable reason to take a starting quarterback prospect. The Titans joined that list after taking Cam Ward first overall. Another large handful of franchises had little motivation to add a quarterback, especially with an early round pick. Those teams weren’t really passing on Sanders. They weren’t in position to render a judgment.

Once the Giants, Saints, Steelers, Raiders and — until the fifth round — Browns passed on Sanders, there were few realistic spots to stop Sanders’s free fall. It’s true that the NFL is desperate for quarterbacks. It’s not true that every team is desperate every year. Plenty of quarterback-needy teams rejected Sanders, but the lack of realistic landing spots this year exacerbated Sanders’s wait.

Now that Sanders is a Brown, perhaps armed with new motivation and humility, he will have a chance to win the starting position among a quarterback depth chart that includes Joe Flacco, Kenny Pickett and Gabriel. Sanders’s skill set should fit perfectly into Coach Kevin Stefanski’s play-action heavy passing game. The illusion that accompanies the draft is gone, replaced by both cold reality and promise. The NFL told Sanders what it thinks of him. Now he can show the league what he really is.

Over much of the past decade, the 49ers have placed one principle at the core of their roster building: They trust Coach Kyle Shanahan will build an elite offense through sheer schematic design, and so their Super Bowl prospects hinge on whether they can build a talented defense.

The 49ers lost a cavalcade of defensive players in free agency, and they threw almost every draft resource they had at rebuilding on that side of the ball around linebacker Fred Warner and pass rusher Nick Bosa. The Niners drafted defensive players with their first five picks, starting with high-upside Georgia pass rusher Mykel Williams, mammoth Texas defensive tackle Alfred Collins and speedy Oklahoma State linebacker Nick Martin.

The 49ers have arrived at a precipice, their contention window narrowing as the players who built their NFC title teams age and grow more expensive. They have to pay quarterback Brock Purdy an onerous extension. Tight end George Kittle has skipped some offseason practices while discussing an extension of his own. Replenishing their defense with young, inexpensive defenders will be crucial for San Francisco to pry open its window for just a little longer.

Ben Johnson arrived in Chicago from Detroit as the NFL’s most coveted coaching candidate, charged with recreating his powerful, flashy offense around last year’s first overall pick, Caleb Williams. Johnson and General Manager Ryan Poles got some ammunition early, using the 10th pick on Michigan tight end Colston Loveland and then trading up for Missouri wideout Luther Burden III, one of the most explosive receivers in the draft.

With Loveland, Burden, DJ Moore and Rome Odunze, a first-rounder last season, Johnson has a chance to regenerate the multidimensional attack that made the Lions one of the best, most thrilling teams in the NFL. And don’t overlook seventh-round running back Kyle Monangai out of Rutgers — he was a hyper-productive, bruising runner who played behind overmatched offensive lines.

Having traded for guard Joe Thuney and signed center Drew Dalman during free agency, the Bears entered the draft without a pressing need on the offensive line. Still, one of their most important picks may be second-round offensive tackle Ozzy Trapilo. All the weapons around Williams won’t matter if Chicago, like last season, can’t protect him. But the Bears are building a potentially elite offense for Johnson.

The draft can be a snapshot of the state of college football. No figure is more telling than this: 26 of 32 players chosen in the first round played in either the SEC or Big Ten. Those conferences have expanded and almost become their own tier within the FBS. Talent also trickles up with the transfer portal, meaning the best players are more often going to wind up at the biggest (and highest-paying) programs.

Talent can still come from anywhere, and the first two picks came from Miami (Cam Ward) and Colorado (Hunter). But the draft domination of the SEC and Big Ten seems like a trend that’s only growing to expand.

It’s possible no team had a more coherent draft than the New England Patriots. They needed to better care for Drake Maye, the third overall pick last year who showed promise as a rookie despite a horrendous offensive line and skill players bereft of playmaking. Under new coach Mike Vrabel, the Patriots immediately addressed Maye’s supporting cast.

The Patriots used the fourth overall pick on LSU left tackle Will Campbell, whose four years of excellence against SEC pass rushers will likely win out over concerns about his shorter-than-desired arms. In the second round, they added Ohio State running back TreVeyon Henderson, perhaps the best explosive-play running back in the entire draft, providing Maye a path toward easy yards that were absent last season. Third round wideout Kyle Williams from Washington State is a burner who should complement free agent signee Stefon Diggs.

Given their talent injection on offense and upgrade at head coach, the Patriots are a candidate to make a Commanders-like leap from the bottom of the NFL to playoff contention. They would have had the first pick if they hadn’t beaten Buffalo in a meaningless Week 18 matchup. But they made the most of the picks they ended up with.